Chicago Classical Review

It’s not your imagination: this April is indeed the coldest in Chicago in 130 years. But Riccardo Muti’s program with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Thursday night served up considerable heat, offered a lineup of French and Russian showpieces that added up to more than the sum of their parts.

None of the four works performed–two each by Debussy and Tchaikovsky–are so obscure that they can be called rarities. But neither are they regularly heard either, for various reasons. The program in its music and ordering had a European festival quality to it—not necessarily a bad thing, especially when played with the kind of brilliance and conviction the CSO routinely brings to such repertoire under their Italian music director.

Claude Debussy’s Nocturnes has not been performed complete downtown in a decade and led off the evening. One doesn’t associate Muti with French repertory but it would be hard to find a more organic, atmospheric rendering of the opening “Nuages” (Clouds) than that heard Thursday night. Unhurried, flowing and evanescent in the slowly swirling textures, the quietly terraced playing of the musicians was extraordinary even by local standards–not least the languorous half-tones from Scott Hostetler’s English horn. The effect of the performance was quietly magical and wholly captivating, drawing the audience in like a symphonic “il était une fois…”

Jarring contrast was provided by the start of the spirited “Festivals,” albeit with some blare from the overloud brass. Characteristically, Muti found an idiosyncratic quality even here, with the harp chords that presage the middle martial section having an oddly ominous quality.

The closing “Sirenes” section was nearly as striking as the opening “Nuages.” The women of the CSO Chorus were arrayed across the back of the stage, claustrophobically positioned between the back wall and the rows of brass and percussion. If their initial singing was a bit overly robust, in the latter sections the women conveyed the sirens’ eternal mystery of the sea with unanimity and finesse, maintaining immaculate intonation as their wordless–and mercilessly exposed–vocalise slowly receded to silence.

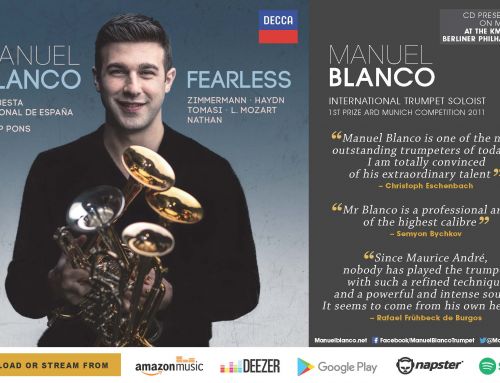

Here too Muti brought out the undulating strangeness in the orchestra, something mysterious and unsettling. The hushed sensitivity of the playing was once again striking, including that of the guest principal trumpet, Manuel Blanco, of the National Orchestra of Spain.

Principal harp Sarah Bullen performed Debussy’s “Sacred and Profane Dances” Thursday night. Photo: Todd Rosenberg

A Debussy morsel followed with the Sacred and Profane Dances. Despite its title, the work is not one of sharp dramatic contrast so much as a nine-minute moderato miniature for harp and small string ensemble.

CSO principal harp for the past 22 seasons, Sarah Bullen assayed the first dance (with the contradictory marking “very moderate”) with typical polish and facility, albeit in a straightforward, even brusque manner that somewhat diluted its intimate charm. She found more of the score’s delicate whimsy in the ensuing section, with Muti and her string colleagues lending refined and piquant support.

Music of Tchaikovsky made up the second half with a pair of contrasted works offering choice opportunities for big-boned color and brilliance from Muti and the players.

Though similar in structure to his popular Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture, Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini is a grander, darker work. The tone poem is inspired by Dante’s tale of the woman who indulges in an adulterous affair with her brother-in-law, and the lovers are consigned to ride the winds of hell for all eternity.

There was an uncharacteristic lack of grip in the opening section, yet the performance soon found its footing, with Muti going airborne as he whipped up a cataclysmic depiction of the howling winds of hell. Stephen Williamson’s clarinet solo was duly compelling and enigmatic, as it leads in to the love (or lust) theme, a melody both soaring and unsettling. The strings gave unapologetic richness to the theme’s climax. In the final section, Muti led a seismic reprise of the sinners’ maelstrom in a coda that could likely be heard on Michigan Avenue.

And so, from hell to dancing.

Muti closed the evening with a generous half-hour suite of excerpts from Swan Lake. Once regular repertory, the suites from Tchaikovsky’s ballets seem to have gone out of fashion in concert halls over the last half-century, the music perhaps regarded as too light or unsubstantial for serious concert fare.

But not everything has to be Gurrelieder. Tchaikovsky’s ballets contain much glorious music and deserve to be heard more often than is afforded by the occasional ballet company revival.

Sitting in for his third week in a row, Mingjia Liu–principal of the San Francisco Opera–launched the famous oboe theme of the opening Scene with pure if somewhat unfocused tone. The ensuing Waltz–Tchaikovsky’s most memorable–was aptly elegant and flamboyant in Muti’s unapologetically ripe reading.

The various character dances were mesmerizing, thrown off with fizzing panache and affording opportunities for many front-desk players. Concertmaster Robert Chen floated beautiful, golden-toned violin solos in the pas de deux, with John Sharp’s ensuing cello line just as fetching. Blanco delivered trumpet playing both nimble and dazzling in the flashy pyrotechnics of the Neapolitan Dance.